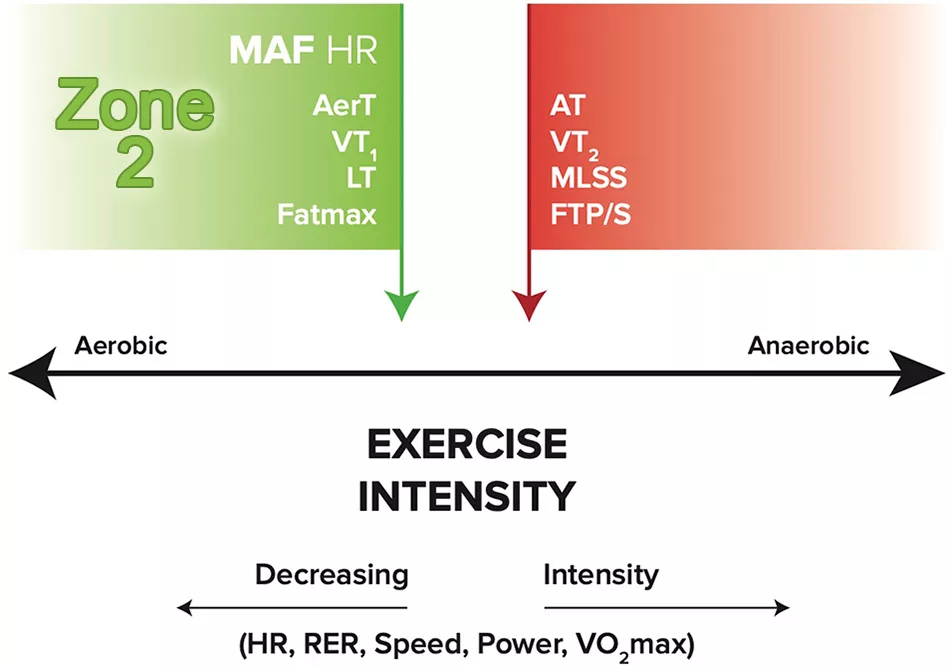

Figure 1. General relationships between Zone 2 aerobic (MAF HR, AerT, VT1, LT, and Fatmax), anaerobic (MLSS, FTP/S, VT2, and AT), and exercise intensity (HR, RER, speed, power, and VO2max). Green arrow indicates maximal fat oxidation; red arrow indicates reduced fat oxidation. MAF HR, maximum aerobic function heart rate; AerT, aerobic threshold; VT1, first ventilatory threshold; LT, lactate threshold; MLSS, maximal lactate steady state; FTP/S, functional threshold power/speed; VT2, second ventilatory threshold; AT, anaerobic threshold; RER, respiratory exchange ratio; VO2max, maximal oxygen uptake.

What is Zone 2 Training?

Zone 2 training, also known as aerobic base training, is the art and practice of exercising at your Zone 2 intensity (Figure 1). It has been known since the days of Arthur Lydiard in the 60’s for runners, and Tour de France riders and their coaches at about the same time, that spending substantial training time at your Zone 2 intensity is an effective means of improving cardiovascular endurance, the ability to oxidize fat as fuel, and enhance performance. Aerobic energy is the foundation of life, so anything that improves this function is going to be helpful for just about whatever you do.

Where is Zone 2?

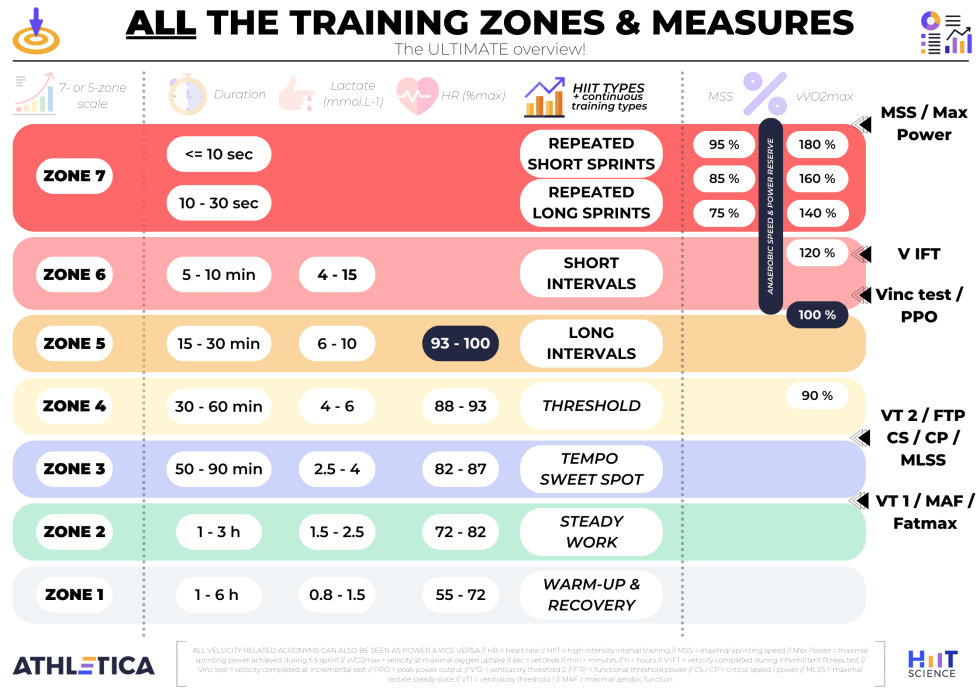

Your Zone 2, on a 5 or 7-zone model, typically sits around 72-82% of maximum heart rate. For context, we show all the potential exercise training zones used in Athletica’s 7-zone model for reference in Figure 2. Zone 2 training is highlighted in green.

Figure 2. Training zones used in Athletica, reference intensity landmarks, typical training formats used, effective time in zone, and percent of maximal heart rate. Zone 2 highlighted in green.

As Martin and I discuss in Chapter 8 of our HIIT Science book, many of these training intensity zone cut-offs have been arbitrarily defined by coaches and not necessarily tied to physiology. But Zone 2 actually is. The transition point from Zone 2 into Zone 3 can be determined in the laboratory as our aerobic threshold — or more specifically, the first ventilatory threshold (VT1), or lactate threshold.

At this point, we start breathing faster relative to how much oxygen we’re consuming. We do this to rid our body of excess CO2 being produced by our working muscles as they use a bit more of the sugar burning pathway glycolysis for energy production. The byproduct is lactic acid. Bicarbonate (think baking soda) in the blood buffers the acid to form water and CO2, which we expel from our lungs. Importantly, this crossover point of intensity, from Zone 2 into Zone 3, is the first sign of increased stress in the body.

I should also mention that this entire Zone 2 craze has been promoted for decades by HIIT Science health chapter author and colleague, Dr Philip Maffetone, and we published this work earlier in a Frontiers in Physiology article in 2020. Phil has termed this point maximal aerobic function (MAF; shown in Figure 1). But today, its all Zone 2!

What about an example?

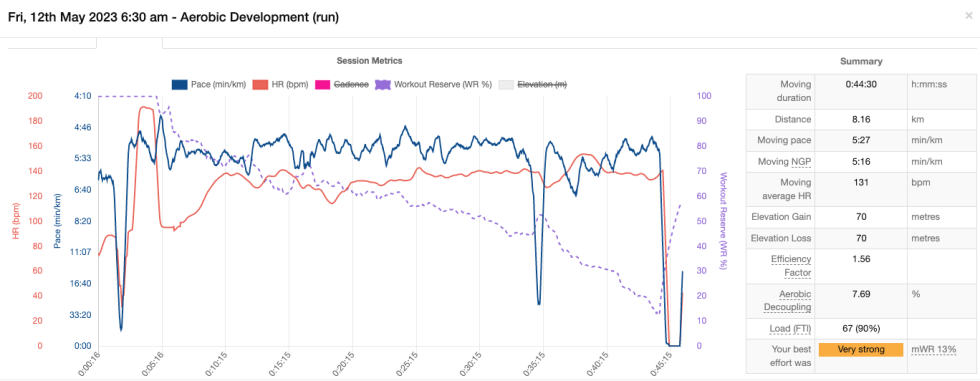

Here’s a really simple Zone 2 aerobic development run on Athletica shown in Figure 3. Notice how the athlete keeps their Zone 2 heart rate and pace throughout. Simple. Importantly, and this mistake gets made often, but if heart rate is drifting too much above that Zone 2 level you should slow down. Why? The answer in the next section.

The stress of work above Zone 2

One of the key papers I mentioned in my talk about stress above Zone 2 was one conducted by Stephen Seiler and colleagues in 2007 titled Autonomic Recovery after Exercise in Trained Athletes: Intensity and Duration Effects. In the study, Stephen and his colleagues took very highly trained runners and got them to do four different sessions as follows.

- Zone 2 for 1 hour

- Zone 2 for 2 hours

- Zone 3 for 1 hour

- Zone 5 for 1 hour (HIIT session)

They measured heart rate variability (HRV), a non-invasive measure of autonomic function (i.e., stress) for 4 hours following every session.

What did they find?

The striking finding from the study was that it didn’t really matter much from an HRV standpoint how much Zone 2 work the athletes did. Even though they did two times the work in Zone 2, their body wasn’t more stressed about it. Conversely, Zone 3 (threshold) or Zone 5 work (above VT2) was associated with autonomic disturbance (i.e., stress). This is highlighted in their Figure below where you can see the lower HRV (more stress) in both the Zone 3 and Zone 5 training session examples compared with the two higher HRV responses following long and short Zone 2 work.

Figure 4. Data from Seiler et al. (2007) showing the heart rate variability (HRV; RMSSD) response following 4 different workouts in highly trained runners. Workouts were done in Zone 2 (below VT1) for 1 and 2 hours, in Zone 3 (threshold) and intermittently above VT2 as high-intensity interval training (HIIT – Zone 5). Note the low stress (higher HRV) of Zone 2 work irrespective of duration.

So the first point of importance when it comes to Zone 2 work is that in the context of the body’s autonomic nervous system, it isn’t overly stressful. You can do a lot of it and it will be relatively easy on your system. And remember the key principle of consistency. That is:

the most important training session is the next session.

Zone 2 allows you do do the next session because it isn’t overly stressful. In contrast, work above Zone 2 is going to take its toll. That’s not to say there’s anything wrong with top zones, as they are super important also, only that you need to be more careful around how much time you are spending in them.

What are the benefits of Zone 2 training?

So now that we know we won’t get too stressed by Zone 2 training, let’s now get clarity on its benefits. There’s many, and these are summarized in the infographic below (Figure 5).

- Cardiovascular development: Training in this zone improves the body’s ability to deliver and utilize oxygen efficiently, increasing cardiovascular endurance and fatigue resistance. On Athletica, keep an eye on your efficiency factor (EF) and aerobic decoupling parameters.

- Fat burning. This is the big one. Relative to carbohydrate metabolism, there are only clean energy byproducts – water and CO2. Working in Zone 2 primarily relies on fat metabolism as the energy source as the intensity sits right around the point of maximal fat oxidation, termed FatMax.

- Recovery and injury prevention: Training at a moderate intensity puts less stress on the body compared to higher-intensity workouts, allowing for better recovery and reducing the risk of overuse injuries. The higher your fat metabolism, the better your immune system functions to recover you.

- Base building: Zone 2 training is often used as a foundation for more intense workouts. By developing a strong aerobic base, athletes can enhance their performance in higher-intensity training zones. We showed this in another study from Stephen Seiler’s lab where athletes with a higher aerobic base leveraged their fat burning advantage to produce better quality HIIT (Hetlelid et al., 2015).

- Better use of fat as a fuel across everything you do: As a recent paper highlights, many athletes operate in a carbohydrate-reliant high stress state. By shifting towards more use of fat as a fuel across exercise training and life, athletes become healthier, recover better, lower inflammation, reduce hormonal stressors and lower the chance of overtraining or maladapting to training. Zone 2 training is one of the key levers you can pull to allow this to happen (Maffetone & Laursen, 2016).

Figure 5. A summary of just some of the many benefits of Zone 2 training. With consistent and progressive Zone 2 training we see improvements in cardiovascular endurance and endurance performance, as explained by enhanced fat metabolism (more mitochondria). These improvements are associated with better immune function, lowered inflammation, improved sleep, better recovery and lowered autonomic stress.

Summary

In short, Zone 2 training should be an important component of nearly all training programs. Of course, you’ll find Zone 2 sessions heavily featured throughout your Athletica training plans to help you facilitate these benefits and enhance your health and performance.

References

Hetlelid KJ, Plews DJ, Herold E, Laursen PB, Seiler S. Rethinking the role of fat oxidation: substrate utilisation during high-intensity interval training in well-trained and recreationally trained runners. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2015

Laursen PB, Buchheit MB. (2018) Science and application of high-intensity interval training. Solutions to the programming puzzle. Human Kinetics Publishers. Champaign IL.

Maffetone PB, Laursen PB. Athletes: Fit but Unhealthy? Sports Med Open. 2016 Dec;2(1):24.

Maffetone P, Laursen PB. Maximum Aerobic Function: Clinical Relevance, Physiological Underpinnings, and Practical Application. Front Physiol. 2020 Apr 2;11:296.

Seiler S, Haugen O, Kuffel E. Autonomic recovery after exercise in trained athletes: intensity and duration effects. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007 Aug;39(8):1366-73.